Brian May vs the Shredders: How He Sees Steve Vai, Joe Satriani—and the Queen Fight That Shaped a Classic

Melody vs. Fireworks: Where Brian May Stands Next to Vai and Satriani

Put three world-class guitarists in a room—Brian May, Steve Vai, and Joe Satriani—and you get three completely different approaches to the instrument. May is melody-first, a composer on six strings who builds choirs out of guitars. Vai and Satriani are precision pilots of speed, nuance, and control, pushing technique to its limit. There’s overlap, sure, but they’re playing different games.

May’s calling card is the Red Special, the homemade guitar he built with his father from fireplace wood. He tends to use a sixpence as a pick, leans into a treble booster, runs into Vox AC30s, and stacks harmonies like a studio arranger. Think Brighton Rock’s cathedral-like solo, the soaring orchestrations in Killer Queen, or the fanfare textures on Procession. He isn’t trying to win a speed contest. He’s after drama, counterpoint, and singable lines that survive when you strip the song down to a single melody.

Vai and Satriani, meanwhile, raised the ceiling for what a guitarist can do in real time. Satriani’s legato and modal control—Lydian tones on display in Always with Me, Always with You or the glide of Surfing with the Alien—turn a solo into a lyrical monologue without a singer. Vai bends the rules of physics: expressive whammy bar dives, alien harmonics, elastic vibrato, the kind of control you hear in For the Love of God. Technically, they live in zones where rhythm subdivisions, fretboard mapping, and wide-interval ideas are daily language.

May has repeatedly praised players like Vai and Satriani over the years while stressing that his own lane is different. That’s not modesty—it’s accurate. His expression is compositional. He writes parts that act like horn sections and strings. He layers three, five, nine guitars until they sound like one voice, then leaves open space for the vocal. It’s why a few notes from We Will Rock You or a single bend in Somebody to Love say more than a flurry of runs ever could.

There’s also a performance philosophy at work. May’s live rig often uses timed delay to create rhythmic canons—one phrase chasing another across the stereo field—so the solo becomes a conversation with itself. Vai and Satriani, by contrast, tend to make the conversation between the hands: tapping, wide slides, rapid-fire sequences, and picked staccato that flips meter on its head. Different toolkits, same end goal: goosebumps.

The Queen Tensions: When Freddie and Brian Pulled in Different Directions

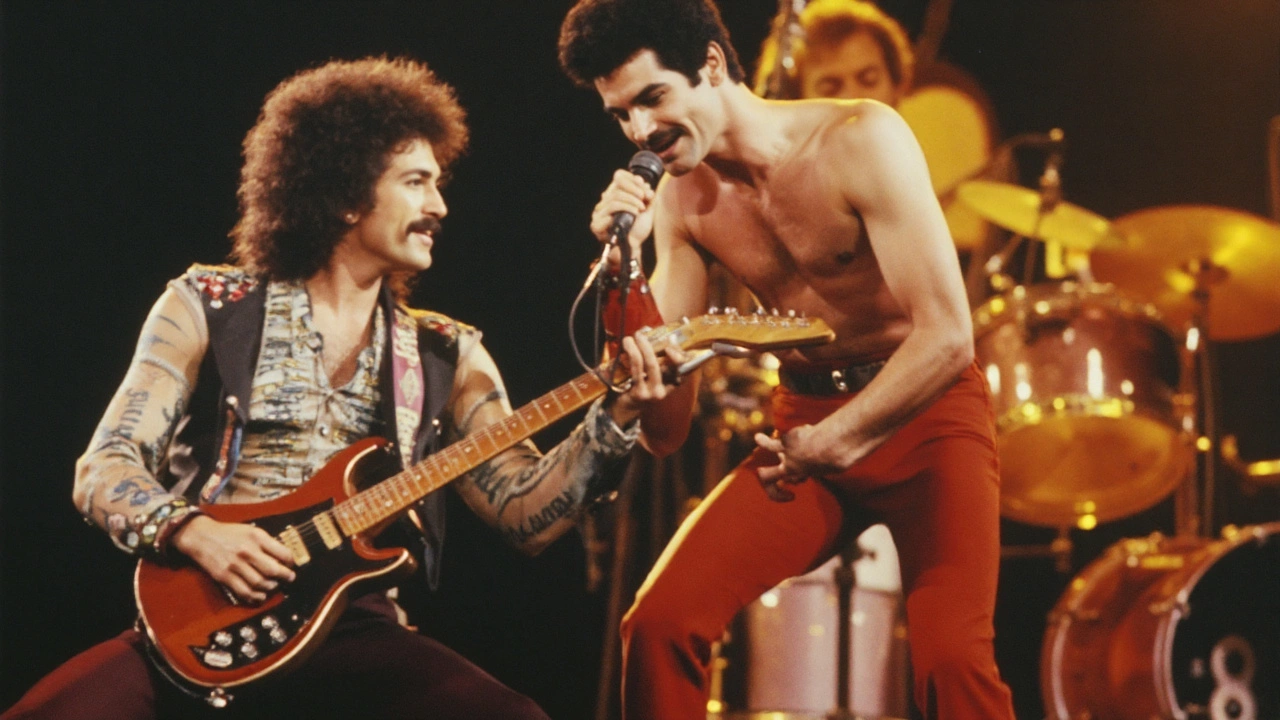

Queen worked because it was a tug-of-war. Four writers with strong tastes, one brand. Creative differences weren’t a side note—they were the engine. And a few of those differences boiled over around the time the band chased chart-busting grooves.

Take Another One Bites the Dust. John Deacon wrote it, and its pulse is pure bass-and-drum minimalism. Freddie Mercury loved the sleek, dance-floor energy and pushed it hard in the studio with producer Reinhold Mack. The guitar? Surprisingly sparse. Brian May’s lines are razor-thin by design, more texture than riff. Behind the scenes, there were debates about the track’s direction and whether it should be a single. Several band accounts over the years point to outside encouragement—famously, Michael Jackson telling them it was a hit waiting to happen. Released despite internal hesitation, it became their biggest U.S. single.

That moment wasn’t just a chart story—it marked a fault line. Mercury was excited by funk, disco, and the emerging synth palette. May was rooted in rock guitar as the backbone, even as he adapted to new sounds. You can hear the tug through the early 1980s. Hot Space leaned into dance and R&B textures; live, the band often steered the songs back toward rock muscle. That push and pull wasn’t hostility so much as identity management: How far can Queen stretch and still sound like Queen?

Other classics tell the same story in different ways. Bohemian Rhapsody was a Mercury epic that the label thought was too long and too weird; the band dug in together to release it anyway. One Vision evolved into a group credit after a jam, with Mercury and May sparking off each other in the studio. Radio Ga Ga dialed back guitar in favor of synths, which made it massive on radio while nudging at the edges of May’s comfort zone. The balance kept shifting, and the tension—handled, argued, and negotiated—gave the band range.

What gets lost in the myth-making is how intentional those choices were. May could have filled Another One Bites the Dust with riffs. He didn’t. He played the role the song needed, even when it meant leaving space. That’s a different kind of virtuosity: discipline as a musical decision. It’s also the thread that connects his style to the wider guitar world. Where Vai and Satriani often thrill with what they can add in the moment, May amazes with what he chooses to leave out.

So when people frame it as a rivalry—May vs. the shredders, Mercury vs. May—it misses the point. These were artists with distinct aims, converging on the same target: memorable songs that move big rooms. Sometimes that meant friction. Often it meant magic. And occasionally, it meant a bass line so strong the guitar barely speaks—and still, somehow, steals the show.